Meet Joseph Audette, M.D.

Meet Joseph Audette, M.D.

Course Founder & Director

Joseph F. Audette, M.A., M.D.

My first introduction to myofascial pain and trigger points was a personal one. During my residency at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, I had injured my shoulder doing Martial Arts. In seeking treatment from some of the attending physicians in my program, I received an aggressive set of trigger point injections to my shoulder. These were performed using a technique developed in New York based on the idea of a trigger point as a knotted area in the muscle that had to be “broken up” with repeated thrusts of a large gauge needle. A local anesthetic mixed with steroids was then injected. The technique was painful and did nothing to resolve my ongoing shoulder pain.

By sheer luck, our residency program invited Mark Seem[1], the head of a local acupuncture school, Tristate Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine, to lecture to us about the potential benefits of acupuncture. At the end of the lecture, he asked for a volunteer to demonstrate a particular needling technique that he had developed. This technique had been in part influenced by Janet Travell’s [2] methods of trigger point injections. I raised my hand and underwent my first treatment of trigger point needling. I had a dramatic response and decided to enroll in his school to learn acupuncture and his unique approach to needling using a trigger point model. While at Tristate, I also had the opportunity to meet Kiiko Matsumoto, an internationally recognized master in a Japanese acupuncture approach.

When I moved to Boston in 1995 to start my practice, I continued to study and work with Kiiko.

As I continued to find ways to integrate a “Kiiko-style” of acupuncture with the trigger point needling techniques I had learned from Mark Seem, I began to explore more about Kiiko’s discussions of acupuncture points being similar to a cave. She taught that our role as acupuncturists is to mine the cave to unlock the point to reveal the gold that translates into the patient’s healing. In addition, she advocated finding a point remote from the center of pain to release the painful area indirectly. This technique was effective, individualized, and less painful for the patient.

Of course, Kiiko’s model of the acupuncture point as a cave did not work well with the Travellian style of trigger point needling I had learned. The focus of that style of needling was to find a knotted area in the muscle, also called a myogelosis. By needling this area aggressively, the muscle would often exhibit a “local twitch response,” a strong reflex contraction of the muscle fibrils. This twitch response would allow the muscle to relax, thereby helping to restore normal muscle function and resolve the pain issue. However, there were many problems with this approach. Firstly, the technique was often very uncomfortable for the patient to undergo. Also, there were typically multiple muscles that needed this treatment method to resolve the patient’s issue. For example, in the case of my original shoulder problem, there were at least five muscles that required treatment. Not everyone tolerated this approach. During treatment, if the patient tensed up related to the aggressive nature of the approach, the muscle would not twitch and release. In addition, this needling method was very time-consuming for the practitioner.

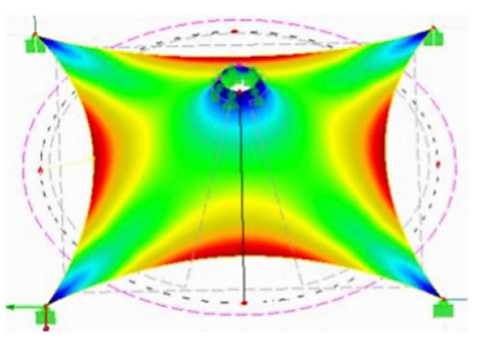

Around that time, I was also exploring architectural ideas and the concept of the beauty and functional harmony of a building being intimately tied to structural integrity, as advocated by Frank Lloyd Wright. There is a direct parallel between the integrity of an architectural structure with that of the human body. In trying to find more connections, I started reading about tensile membranes, and the concept of Tensegrity as conceived by Buckminster Fuller. [3]. The human body with the tension created by the bony or rigid elements separated and interconnected by muscles and fascia that have a spring and tension have almost infinite resiliency when perturbed to rebound back to their original structural form. This relates closely to the underlying theory of Tensegrity. Within such structures, there are nodal stress points of high potential energy that, when deformed, will tend to dimple and create an energy well.

Global deformation of tensile membrane [4]

As I examined the formation of energy wells in the tensile membranes, I was quickly brought back to the ideas of Kiiko Matsumoto. I soon became convinced that the true approach to integrating dry needling into acupuncture was to find these energy wells with a needle, which I called a needle well. At this point, in carefully palpating my patients, I discovered the fascial needle wells where the interconnecting muscles became deformed by the shortening of the muscle fibrils and fascial dysfunction. I started needling in the wells rather than on the most prominent myogelosis. Suddenly, I found that I could create twitch responses in multiple muscle groups with the most minimal needle stimulation with one needle. The technique was surprisingly effective and very well tolerated even by sensitive patients.

This approach has transformed my clinical practice and the way I train my acupuncture students. The technique is easy to learn, extremely effective for patients, safer and much less painful than some of the currently popular dry needling methods, and (as a bonus) time saving for the clinician.

References:

[1] A New American Acupuncture – Acupuncture Osteopathy

The Myofascial Release of the Bodymind’s Holding Patterns, Mark D. Seem, Ph.D. Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO 1993.

[2] Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction, The Trigger Point Manual, 2nd Edition. (2 Volumes) David G. Simons, Janet G. Travell, and Lois S. Simons. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, 1999.

[3] Fuller, R.B. (1961). Tensegrity. Portfolio and Art News Annual. 4:112-127, 144, 148

[4] International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 05 | May -2017